Recently, I went through a pile of old floppy disks (remember them?) to see if there was anything of interest on them and if so, back it up before floppy disk bitrot set in. Sadly, I found that a few disks were already too far gone (or possibly are Amiga disks, so I’ll revisit them next time I have my A1200 up and running), but some have survived.

One of them contained the mid-year interim report for my third year university project from some 16 years ago. Unfortunately, much of my advanced chemical knowledge has been lost over the years, perhaps through some human bitrot, so I don’t even understand some of what I’d written then. Some excerpts:

Aims

There are several things that I wish to achieve in this project. The first is that I want to research what has already been done in the field of silica supported organometallics. This has already been done to a large extent, and it turns out that there has been little written specifically on this topic. Luckily, silica supports in general are well documented, as the examples in the review section show.

I plan to use this knowledge to attempt to graft organometallic compounds onto a silica surface, using similar conditions to those stated in the literature for non-organometallics. These methods need to be (and have been) researched.

This much, I can recall. I was supposed to be finding ways of attaching various compounds to silica by first attaching something else to the silica or the compound to act as a sort of glue.

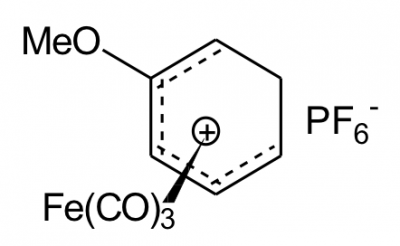

The main organometallic that I wish to attach to silica is:

Tricarbonyl [(1,2,3,4,5-h)-2-methoxycyclohexadienyl] iron (+1) hexafluorophosphate (-1)

Nope. No idea. Thankfully, there’s a diagram:

For simplicity, this shall usually be referred to as ‘the iron salt’.

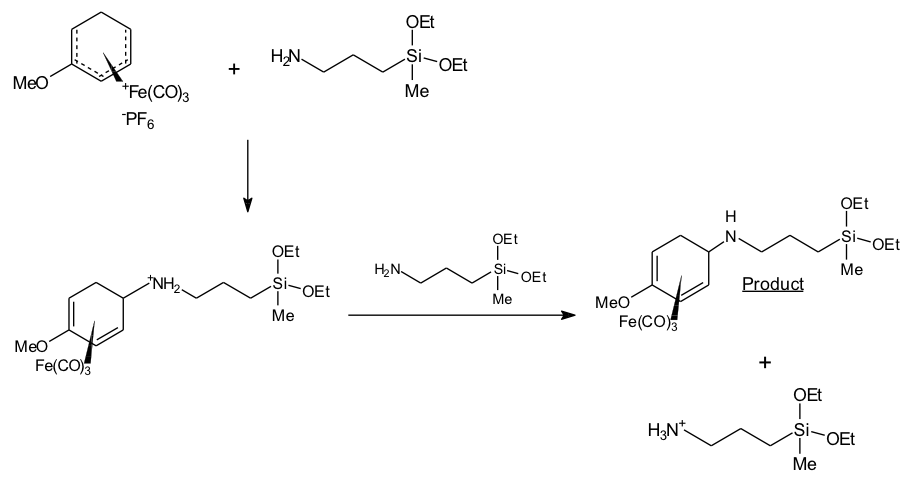

That’s looking more familiar. The document goes on to explain how I’m going to attached this iron salt to the silica, and what I’d already done up to this point. Later on, it shows the exciting looking diagram below, which I remember proudly creating using a PD piece of chemistry software on my Amiga and transferring it to the Word document on my Windows 3.1 PC. Exciting days.

Wow. That was basically just adding the “glue” (the silane group there with the Si in the middle) to the iron salt. I recall taking it down to some very large machines (infrared spectrometers) that could print out graphs showing I’d actually done what the diagram said. Of course, you had to interpret the graphs and so on, but it was very exciting.

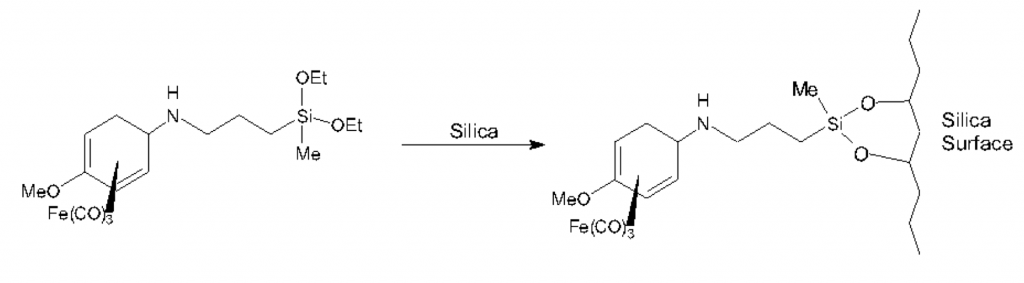

Then I did the thing needed to stick my iron salt with its silane “sticky tail” to some silica. Woo!

Again, large clever machines were involved proving this actually happened. I remember being very pleased with myself. A few more experiments appear in the report, attaching different things and using different glue, but the excitement at the time was planning the experiment, using theory and research to suggest it should work, then being the first person ever to actually go ahead and try to do this thing – and it working first time pretty much exactly as expected.

And what was the purpose of all this? As with most chemistry undergrad research projects, it was all part of a larger plan. My supervisor was working on projects that would use what we had attached to the silica as a sort of indicating device, a detector, or other similar things for use in bioanalysis. A few years later, he published my work as part of a larger paper: http://joam.inoe.ro/arhiva/pdf5_3/Anson.pdf

In fact, some of the work was referenced in another project – eInk. The way it works is supposedly partly due to how functional groups of “ink” are attached to the “paper”, analogous to my work. So in a way, I indirectly assisted in the creation of the Kindle. You’re welcome.